A Prolegomenon on Olympus

TL;DR

Olympus is a solution to the problem of Mercenary Liquidity.

Bonding is there to amass assets. It delays the Olympus’ payment to buy your assets. And in return for the delay, it pays you more.

Staking is there to prevent price dumps.

An Ohm-fork would be rid of its ponzinomicality once it generates income.

Olympus is still a long way away from becoming a reserve currency, and will likely not see the exorbitant privilege enjoyed by the USD.

Olympus could be used as a basic architecture of amassing a treasury to fund projects - like a SPAC.

Memeification is there to persuade people to (3, 3).

Introduction

The innovation that is Olympus DAO has sparked discussion and debate in the crypto community. Yet we still do not have a very clear dissection of what this *thing* actually is. Multiple angles have been offered to explain what it is, what exactly is the problem it solves, and how it works. It is not clear whether all of them are valid explanations.

To illustrate the confusing galaxy of narratives floating around Olympus, it is worthwhile to discuss what kind of explanations someone new to the Olympus protocol, might encounter on his investigative journey of figuring out what the Olympus DAO is.

First, one would encounter the claim that Olympus is a protocol that aims to become “the reserve currency of the crypto world” - as proclaimed in their own docs. But what exactly does that mean? And how would that even look like…? This question is never really quite explored, and not before long, One would read people saying that it is just a pure ponzi, and that there is nothing here. After all, where on earth is the yield coming from? And if one had stayed interested a little bit longer, one would encounter the claim that Olympus DAO is an innovative solution to the problem of Liquidity Rental. And then one might also encounter bizarre and cryptic claims that new crypto projects could use the OHM mechanism to build treasuries. And then, one might encounter arguments comparing the US government to the Olympus DAO protocol, but whether they’re half-baked one could not tell. Confused and tired, one ultimately does what one does best - one apes into the protocol and goes to bed.

Just what is Olympus DAO good for? That is the question one tried to figure out. And this is the question I shall endeavour to answer. As usual, citizens of the crypto universe, do your own research. I will not explore the question of how to model Olympus. For that, one can reference the ELI5 for Olympus Dashboards community doc, Asfi’s Bankrun Simulation, and Jack Melnick’s Olympus DAO: DeFi’s Answer to Mercenary Liquidity.

The Problem of Liquidity Rental

We will not approach Olympus from the “reserve currency” angle, though it is the most widespread and immediate answer offered to the question at hand. The reason is that the “reserve currency” angle is actually rather confusing, and does not offer an easy way to understand Olympus’ protocol design.

The most plausible and comprehensible good that Olympus does, is that it offers a solution to the Problem of Rented Liquidity, also known as the Problem of Mercenary Liquidity. Olympus’s protocol design is motivated by this problem.

What is liquidity? It is the ease of swapping one token for another. If a token cannot be easily swapped, it is said to be illiquid, or that the pair lacks liquidity. In 2020, the innovation that is the Automatic Market Making (AMM) has solved this problem, by the x*y=k curve that we are all familiar with, where x and y are the initial capital provided, and \sqrt(k) can be understood as “liquidity”, as in here. The issue is that to get people to provide the x and the y to make up the liquidity, you have to incentivise people. Compound found the first incentivisation mechanism: give out reward tokens to suppliers and borrowers in the lending markets. And out of this, came yield farming, which is the act of strategically moving capital to chase the highest liquidity provider rewards.

This act of giving out rewards to people who are providing your liquidity, is called liquidity rental, or mercenary liquidity. And it is expensive, unsustainable, and unhealthy to a project’s development. People would just withdraw from the liquidity pool as the rewards dry up. The rewards have to dry up as the project who is giving out the rewards to incentivise liquidity is literally giving out money - the tokens can actually be sold on the market for something. If the project doesn’t want to run out of tokens to give out, well, they can mint them en masse - but that destroys the value of the rewards. In either case, LPs would eventually leave.

If that wasn’t clear enough, it’s always useful to employ the vending machine analogy to understand what a particular smart contract is doing. The AMM is like an airport coin exchange machine. But unlike vending machines we are familiar with, the inventory (the coins) in the vending machine is supplied not by staff. It is to be supplied by the public. And to incentivise the public to supply it, this vending machine gives you small reward tokens for supplying the machine. Kids then noticed it’s best to move the money you supply these vending machines around to maximise the value of the tokens you get - that’s yield farming.

Olympus’ solution to the Problem of Liquidity Rental is simple: own your own liquidity. How? Buy it? With what? Your own token. What’s it called? Ohm.

And thus, the problem of how to secure liquidity is transformed into the problem of how to build value for your token - which is a problem well-understood, and one with many solutions - all of them go by the name of “income”.

This answer to one’s Question should be satisfactory, though we have yet to explicate how Olympus fulfils this purpose. If you are interested in more in-depth discussions of the Problem of Liquidity Rental, I would recommend Joey Santoro’s New Approaches to Liquidity in DeFi, which discusses not just the problem but also different solutions aside from Olympus, such as Tokemak and Fei. Nat Eliason’s I Was Wrong About Olympus, and Owen Fernau’s DeFi 2.0 Wave of New Projects Test Liquidity Mining Alternatives are also both worthwhile reads.

Why Bonding?

So Olympus buys the liquidity of a token with Ohm. But it doesn’t just pay you right here and then. Nor does it pay you the exact value of the LP tokens in Ohm. It does two things: (1) it pays you later, (2) and they pay you more than the value of your LP tokens.

This is called bonding. As Introducing Olympus Pro puts it: “Bonds are a mechanism by which the protocol itself can trade its native token in exchange for assets. Instead of renting liquidity from third parties, it purchases them outright.”

I’d like to offer some intuitive colour here. Why introduce bonding? Well, if Olympus purchases LP tokens by simply giving you the equivalent value of Ohm, and by giving it to you now, then nothing new has been introduced - actually, such a mechanism is just an exchange of the LP tokens with Ohm.

However, the vesting characteristic of bonding, constitutes a time shift, a lending mechanism. In fact, the fact that when you bond, you get an amount of Ohm calculated based on a discounted value of Ohm, means, in practical terms, you have earned interest on your bond. So in a sense (2) could be seen as a corollary of (1).

But why does Olympus have to defer the release of Ohm? I.e.: why is (1) necessary? Olympus’ own medium article Dai Bonds: a more effective Sales Mechanism offers the answer: “Bonds defer market impact of new supply. OHM from bonds slowly becomes available as the bond vests. This spreads out the distribution of this new supply, in contrast to sales which give the OHM to the purchaser at point-of-sale. Sales also create a quick arbitrage opportunity (buy from protocol at discount and sell into the pool) that would increase volatility.” So the logic is this: if the Ohm is immediately released, then you cannot sell them for a discount. Because if you sell OHM for LP at a discount, traders can buy that Ohm at a discount, sell OHM to OHM-X (where X is any token) pool for profit, thereby looting the OHM-X pool reserves of X. So, (1) is a corollary of (2), i.e. (1) iff (2). If you affirm (2) then you must affirm (1), and vice versa.

So why is (2) necessary? This is simple. Because at its initial offer, Ohm is trash. It is a currency invented out of thin air. It has no value. To accumulate value, it must reward. Hence bonding discounts are necessary.

Bonding also improves the quality of the exchange experience as it ensures much deeper liquidity and therefore smaller slippage, as discussed in this dune dashboard here.

Why Staking?

So why staking? And why give such a ridiculous APY to stakers? Where does the APY come from?

Let’s talk about the origin of the yield. The APY comes from the Ohm printed by the Olympus protocol. But this is not printed out of thin air. The Ohm is printed based on how much value there is in the treasury. In particular, each Ohm is backed to one 1 DAI - i.e. if the sky fell on our heads each Ohm would at least be exchangeable for 1 DAI. When each Ohm is backed by more than 1 DAI, more Ohm would be printed and distributed.

The reason why staking is implemented, is to prevent people from selling. If you sell, your punishment is that you miss out the staking rewards. This means staking is here to prevent you from selling, which keeps the price of Ohm high. And it is the consistent high price of Ohm that makes the discounted Ohm earned by bonding valuable. And it is this bonding drive that keeps liquidity high, and assets flowing into the treasury. If there had been no staking reward mechanism, bonders would immediately sell their Ohms immediately upon receiving them.

This is as Ryan Watkins put it in his tweet, it creates a flywheel, a virtuous circle that keeps Olympus going up.

We have now established the entire architecture of Olympus, which is summarised in this flowchart here.

In particular, I have labeled “money” with a lighter green and Ohm in a darker green. The relation between “money” and “ohm” to bear in mind is that “Ohm” is standing in for a currency whose value is questionable, where “money” is standing in for something with more asset value. Ohm is trash, and FRAX is the US dollar. The design of Olympus was to transmute Ohm into something valuable.

Note that if bonders stopped bonding, and stakers stopped staking, then this whole mechanism would reduce into a simple liquidity provider.

Ponzinomicality

Without diving into mathematical demonstrations, I will segway here into a comment about Olympus’s ponzinomicality. I will define a ponzi scheme as a structure in which profits of early participants are derived from later participants.

Using this definition, we can say for sure that it is not true that earlier stakers profit off from later stakers. If that were true, then early stakers would welcome more stakers to come in. But this is clearly not the case. There is no situation in which early stakers would welcome any influx of stakers because such an influx of stakers would dilute the rebase rewards: more stakers, less reward per staker.

Where does the profit for stakers come from? From the rebasing, which comes from bonders putting assets into the treasury. If every staker is a bonder, then clearly the first staker earns the rebase from the second bonder, the third bonder, and so on.

This is where things get ponzinomical. Not only that, recall the fact that bonders are promised Ohm. So Olympus has to give out Ohm to both bonders and stakers. If Olympus satisfies this by merely printing Ohm then the price of Ohm will collapse - just like any old ponzi.

Why do ponzis collapse? It is because profits for participants come exclusively from the capital contributed from later participants, and they must eventually exhaust all further participants to incorporate into the scheme. However, if the Ponzi scheme is able to find a new source of income, and use that income to reward all those in the scheme, then the ponzi will be successful.

Up till now, the only income Olympus has we’ve described is through bonding. Of course, Olympus also earns the LP fees from the LP tokens it locked up in its treasury. Given that, the only question then is whether that income is sufficient.

Olympus as a New Funding Model

It has been hinted in various inconspicuous corners of twitter that Olympus may be used to fund new projects.

https://twitter.com/jonray/status/1467716167796203522?s=20

How may that work?

One just needs to take a look at the treasury of Olympus. If Olympus is providing Liquidity and earning LP fees from the pools they’re providing liquidity to, that structural relation would be provided even if that liquidity, i.e. that money, is deployed to do something else, as long as that something else promises returns.

For example, there’s no reason why OIympus cannot deploy that money to various protocols in the crypto universe to earn returns algorithmically. There’s no reason why Olympus cannot deploy its treasury to do something like Yearn. But if it can, there’s no reason for Olympus to not use its treasury to fund the development of a project of its own liking. But if Olympus can do it, there’s no reason why someone who wants to fund their own project cannot just fork Olympus’ code base, go through the whole initial 8-figure APY phase, amass a treasury, and then use that treasury to fund their project’s development. In fact, Temple is doing just that, as shown.

In that case the structure of that project would look like this.

But if the treasury could be deployed to fund the building of a project - to pay for the devs, the contract coders, the BD managers, the community managers, and the meme artists - the treasury could equally be used to buy up another project altogether. And that would essentially turn the Olympus-fork in question into a SPAC. In a sense, KLIMA DAO’s structure is SPAC-like, for the whole project has but only one goal - to acquire BCT. The fact that KLIMA is a Ohm-fork, a financial machine, but one programmed to achieve a social cause, demonstrates that Olympus is a protocol that one can fork to fund practically any project of one’s choice. However, recall the above discussion on ponzinomicality. If an Ohm-fork does not manage to generate income, it will remain a ponzi. Pinnochio’s transformation into a real boy fails. Knowing this sheds some light on the current languishing development of Klima which stands in contrast to its original hype - there is no clear income stream for KLIMA. You drive up the price of BCT, but what next? Can you be sure to sell the BCT at a price higher than you bought it? And what can you do with it right now exactly? Perhaps given some time, Carbon DeFi will mature, and there will be more ways for KLIMA to generate income - but until that day comes, KLIMA’s transformation from Pinnochio into a real boy remains incomplete.

Naturally, as the crypto community matures in its understanding of Olympus forks, this paradigm and analysis framework will become more and more widespread, and the enthusiasm for Ohm-forks shall stabilise and reach its natural equilibrium.

OHM as the Crypto Reserve Currency

Now let us turn to the reserve currency issue. Can Olympus become the reserve currency of the crypto world? How does its innovative bonding and staking mechanism help? What would such a world look like?

Perhaps it might help to answer the question of what is the reserve currency in crypto right now. And to do that we would have to know what’s the definition of a reserve currency.

In the TradFi world, a reserve currency is defined as “a reserve currency is a currency held in large quantities by governments and institutions. These currencies are used as a means of international payment and to support the value of national currencies.”

If becoming “the reserve currency of the crypto world” is interpreted as “becoming the US dollar of the crypto world”, transplanting the characteristics of the US dollar into their crypto equivalents would suggest that Ohm would have to become:

the preferred currency of transaction denomination and pricing in DeFi,

the preferred safe haven currency - the preferred currency in which people rotate into in times of crisis,

the preferred store of value - the preferred currency of retail Hodling, and the preferred currency of accumulation by DeFi protocol treasuries and reserves, including Ohm forks,

a multi-chain currency, complete with all the properties associated with a reserve currency on all chains,

In concrete terms, this would mean that whenever people transact, they will have that transaction to be priced in Ohm. They would want to hold Ohm in their reserves. They would want to save in Ohm. They would count the monies they have not in stablecoins but in Ohms. Olympus’ vision is a world that is not skeuomorphic - the base currency would not be in dollars.

The fundamental reason why anyone would want this should be familiar to all those in crypto: the Fed. As xh3, an OlympusDAO Partnerships and Policy contributor, said to Okex, “What you want when you hold a stablecoin is to maintain your purchasing power over time, which is actually not possible if you hold something that is equally valuable to fiat money like USD because there is not only supply inflation in the U.S. monetary system but also price inflation. In other words, you just lose over time when you hold fiat.” This is the curse of all stablecoins, be they collateralised by fiat or crypto or uncollateralized that maintain their stability through algorithmic magic. And as long as the stablecoin is so cursed, the inflation unleashed by the Fed shall remain the bane of a crypto world that uses stablecoins as their reserve currency.

If anything, to borrow Gensler’s comment that “stablecoins are like poker chips at a casino”, Olympus’ goal to become crypto’s reserve currency is to displace the USD as the ultimate cash out currency at this massive casino.

This is how I assess Ohm on fulfilling the reserve currency criteria:

It should be clear that for Ohm to become the preferred currency of transaction denomination, it would require the crypto universe to undergo massive infrastructure reconfiguration - relabelling all protocols to denominate their prices in Ohm, changing oracles, and not to mention wrapping if not rewriting a huge number of algorithms in OHM-USD price switches. We would also require a complete psychological flippening in the whole crypto community - including retail! ETH-maxis would still exist for sure, but imagine them agreeing to psychologically account their wealth and transactions in Ohm instead of USD - seems like an extremely tall order. And to say nothing of the Bitcoin maximalists.

Let us go further in our Gedankenexperiment. If we take the oft-discussed analogy of “chains as nations”, i.e. to treat Layer 1 chains as nations, and their gas-paying tokens as national currencies, then Ohm becoming the crypto reserve currency, akin to a US dollar amongst the crypto-nations, must mean that Ohm is to become the denomination currency of interchain transactions. Naturally, there are limits to this analogy, the most important of which is that nations can wage war against each other, and chains, as far as I can tell, do not. Within each nation / chain, the national currency / chain native token will remain the currency in which transactions are denominated, but cross chain activity will be denominated in Ohm.

If the “chains as nations” analogy aptly captures the interactions between chains, it should not be too outrageous to start speaking of the balance of payments of chains. And once we start speaking of that, we can speak of le privilège exorbitant. Will Ohm enjoy the exorbitant privilege that the American Dollar enjoys?

“Exorbitant privilege” refers to the benefits that the United States has due to its own currency being the international reserve currency. Being the international reserve currency, allows the US to not face balance of payments crisis, i.e. it does not need to fear about not having enough money to pay for its imports, because everyone accepts US dollars, and the dollar being a fiat currency, needs to only print the dollar to have dollars to pay for stuff it wants.

Suppose I created an NFT on the Avalanche. In minting that NFT, I have paid the minting gas fees in AVAX. And suppose an ETH-Maxi wants to buy it. Then this Avalanche native NFT would essentially be an import, a good imported into the Ethereum ecosystem. In bridging the Avalanche native NFT over to Ethereum, what’s going on in the accounting of the transaction, is that the ETH-Maxi pays the amount of AVAX I charge him for the NFT in ETH. We agree that the amount of ETH corresponds to the amount of AVAX I’m charging because the USD value of that amount of ETH is the USD value of the amount of AVAX I’m charging. If Ethereum tries to just print ETH for this transaction, the price of ETH would simply dump with respect to the USD. But for the USD, if it pulls the same trick, the price movement is not explicitly visible immediately - and so the US could defer the punishment that comes with devaluation.

Exorbitant privilege betides a currency that (i) is used as the universal price denominator, and is (ii) not 100% backed. By this logic, the ill-fated Bancor wouldn’t have enjoyed any form of exorbitant privilege, if it had been actually released, nor would the SDR. But what it would certainly achieve is the obliteration of the American Empire’s exorbitant privilege.

If this logic is correct, then by the same token Olympus should not enjoy exorbitant privilege. This is because Olympus is 100% backed. It cannot print more money unless there’s an equivalent amount of assets flowing into the treasury.

On the other hand, if Ethereum became the reserve currency of the crypto world tomorrow, and started to massively increase the mining rewards (validator rewards with respect to proof of stake), then it will have a lot more ETH to import assets from other ecosystems priced in the same amount of ETH. Ethereum, as a crypto nation, would be exorbitantly privileged.

Let us now conclude this section with a brief discussion on the similarity of Olympus to central banks.

There have been whispers about similarities between the Fed and Olympus, for example, here at Bankless’s WTF is Olympus DAO. Here, it has been referred to as a “decentralised central bank” in passing, and here, in this mini-thread, and in this essay as well. Hashkey’s Algorithmic Stablecoin - the Holy Grail of next-generation defi sort of discusses the evolutionary history of Olympus-like reserve currency protocols, though not with any elaboration as to why Olympus feels like a central bank.

The fact of the matter is that there is not much similarity between the modern central bank (say, the Fed) to Olympus - at least not enough for one to understand or predict Olympus behaviour.

The modern post-Bretton Woods Federal Reserve has a number of monetary policy tools:

Since Olympus does not lend, none of the policy tools the Fed has maps to Olympus, except for open market operations. Open market operations refers to the act of central banks buying and selling securities from and to private banks. For example, when the Fed purchases long-term bonds, this has the effect of lowering long-term interest rates.

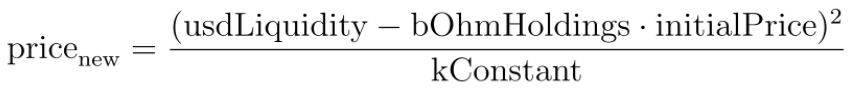

When Olympus changes the BCV, the bond payout, which is essentially the interest paid to bonds, changes via this equation:

So when Olympus decreases the BCV, the bond payout, which can be viewed as interest on bonds, goes up. Interest bonding therefore goes up, and the treasury accumulates assets.

Beyond that there is not much similarity to speak of - at least not until Olympus has lending and borrowing functions.

On (3,3)

One of Olympus’ greatest inventions is the introduction of Game Theory into its design, and the memeification thereof.

In this section, we shall try to establish this: (1) why Olympus’s iconic (3, 3) table is misleading, (2) why inspite of Olympus’ game theoretic structure, we still feel the urge to (sell, sell) and not (stake, stake), and (3) why the memeification is not just for laughs but serves an actual function.

Let us begin with the familiar payoff table that Olympus uses to explain their game theoretic structure. As elaborated here, and here, “the simplest model of Olympus has two players with three possible actions: Stake (Buy), Bond, and Sell”.

If we use this payoff matrix to analyse, then clearly for any player, staking strictly dominates bonding - which makes sense. If you were first to be on Olympus, with a 8 figure APY%, and you have just finished bonding at, and then you decided to bond after getting your discounted Ohm, you’re for sure a dum dum.

So this matrix reduces to

And for this game, the Nash Equilibrium is (stake, stake), for whatever strategy the other player plays, you have maximised your own payoff. This is (3, 3). Staking, under this table, is indeed the dominant strategy. One should note that this payoff matrix is basically prisoner’s dilemma flipped, where “defect” is mapped to “stake” and “confess” mapped to “sell”

But the issue is that this matrix is misleading.

The first thing to point out is that these numbers are made up. We have no reason to believe they actually model the actual payoffs in an actual Olympus - or anywhere close.

There is arguably more mathematical justification and elaboration in the essay Olympus Game Theory, part of Olympus’ official docs, where they approached the issue from an evolutionary game theory point of view.

Evolutionary Game Theory, a sub-branch of Game Theory, assumes there are “generations” of players that “pass off” their strategies genetically into the next round of players. An evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) can then be understood to be a strategy such that if every member of a population is playing it, no other mutant strategy can do better. To put it in another way, a strategy is an ESS iff players playing said strategy get better payoffs than players that adopt a different strategy. Or indeed, a strategy is an ESS if the payoffs of playing said strategy against another player playing the same strategy is higher than playing said strategy against a player playing a different strategy.

Indeed, (stake, stake) is an evolutionarily stable strategy (I have verified this myself). What this means is that if you sell against a staker, your payoff is less than the payoff you would have gotten if you had staked against a staker. If we take the genetic element of evolutionary game theory into the fold, what this means, is that gradually after rounds and rounds of rewards, sellers would be driven to extinction and stakers would remain.

So from whence did our drive to sell come? Is it pure human irrationality at work?

We might be attracted to argue these discussions happen under the assumption that A and B both sell at the same time. This obviously does not capture the “whoever sells first is whoever dumps the price” dynamic we are so familiar with in crypto. If A sells first, he ruins the price for B, which is why everyone prefers to sell first if someone is to sell. But as we shall see, the price dump effect is not responsible for our feeling to sell.

Let us model the game theoretic structure of Olympus.

Consider A and B, who have individually put in 4,000 USD of initial capital, at an Ohm price of 400 USD, to obtain 10 Ohms each.

Let us also assume an Ohm-DAI liquidity pool with the following initial configuration:

Let us also consider only 6 reward periods, where t = 0 refers to before the next reward, and t = 6 refers to after 6 reward rounds.

Using simple x*y=k AMM price logic, we can model how the one party selling would impact the price. To simplify, we will not calculate the price impact based on the extra Ohm he’s earned through staking. We will simply calculate the price impact based on the original amount of Ohms he held - a more conservative number, but it works. In particular, if B sold his share of tokens, the new price A would face would be:

From the perspective of A, this is how the price would be,:

From the perspective of B, this how the price would be:

The payoff for A staking till time = t is therefore:

B’s payoff is similarly derived.

This translates to the payoff matrix of A:

And for B:

As we can see, all Nash equilibria exist on the diagonal - that is, “sell at the same time”. So, incorporating the “price dump” premise does not produce new Nash equilibria.

But one can clearly see that these equilibria are not very stable. Though B has no rational reason to deviate from staking, if B does deviate, the harm to A is massive. If B dumped at t=5 while A staked till t=6, A would have lost 768.37 USD compared to if he had sold at t=5. Game-theoretically speaking, there is no reason for anyone to deviate from staking, for they hurt themselves. But it is precisely this stupidity that causes everyone to second guess everyone and sell earlier than they should lest they become the idiot holding the bag.

To capture our fear of ourselves being front-run and becoming the idiot holding the bag, let us reformulate a simple payoff matrix based on Olympus’s workings, with the following assumptions:

A and B have the same amount of Ohm staked, assumed to be 1

The rebase rate is r, which means thge amount of capital he would have accumulated if he remained staking is (1+r)*p, where p is the price of Ohm;

If A sold, we will assume his selling affects the price of Ohm. We will denote the dump-impacted price as p_{s}

Then the payoff matrix is

But this matrix is paper wealth. If we consider only actually realised gains, then the matrix looks like:

And for this matrix, the Nash Equilibrium is (Sell, Sell). Suppose then users value paper profits with a weight of w and realised gains with with a weight of (1-w), then the matrix looks like

To further simplify, suppose we are extremely charitable and assume no price dump p = p_{s}, and since each period the reward is small, let us put r = 0. Simplifying, we’d obtain:

So people will (sell, sell), as long as w is less than ½ - i.e. if they weigh realised profits more than potential profits. But suppose we flip it - that people do weigh potential profits more than realised profits, i.e. w>½. For example, consider the matrices if w = ⅓ (weigh realised profits more than potential profits)

and w = ¾ (weigh potential profits more than realised profits) after normalisation is as follows.

So (sell, sell) is the Nash equilibrium for w = ⅓ and (stake, stake) for w = ¾. Also observe in changing the weights, the payout in (stake, sell) flipped for A and B. This demonstrates how the weight factor can change the game theoretic structure of Olympus.

One also view w as the confidence factor we have in being able to obtain the unrealised profits without other people crashing. If w = 1, then one is 100% confident in continued staking.

This therefore gives us the reason why memeification played such an important role in Olympus - it is to push w towards 1. This coordination via memeification, could be understood as the “internal coordination” they elaborated in their essay Economic Productivity in Digital Media:

OlympusDAO is the first organization to realize and implement a very significant shift in the application of economic theory. This shift can be expressed in the following way: in digital economy, the economic forces of demand versus supply are generalized into forces of internal coordination versus price coordination. Supply and demand pertain only to price coordination, while entrepreneurship/self-organization (which falls outside neo-classical price theory) pertain to internal coordination. The framework of internal coordination theory is able to explain economic productivity and intrinsic value within the digital economy, as distinguished from the more specific materials economy.

Internal coordination is still underappreciated as a form of economic productivity, with particular relevance to the digital economy. Internal coordination is separate from the forces of supply and demand, and is what equilibrates or regulates supply and demand. Thus, it is what motivates natural self-correction and self-governance by market participants themselves from within the market. The market requires a human being, an entrepreneur, to recognize and solve existing coordination problems, outside of the price mechanism. This happens through the negotiation of social norms. The market is only self-regulating and self-correcting to the extent that common sense norms are negotiated and shared by everyday participants, through internal coordination.

Or to put it as Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal put it so beautifully, the point of memeification of (3,3), is to achieve that very same goal that the great ethicists of history have sought to achieve through the eons: to get strangers to always pick (Stake, Stake).

TL;DR

Olympus is a solution to the problem of Mercenary Liquidity.

Bonding is there to amass assets. It delays the Olympus’ payment to buy your assets. And in return for the delay, it pays you more.

Staking is there to prevent price dumps.

An Ohm-fork would be rid of its ponzinomicality once it generates income.

Olympus is still a long way away from becoming a reserve currency, and will likely not see the exorbitant privilege enjoyed by the USD.

Olympus could be used as a basic architecture of amassing a treasury to fund projects - like a SPAC.

Memeification is there to persuade people to (3, 3).

Follow @noctemn2021 on twitter if you find this useful.